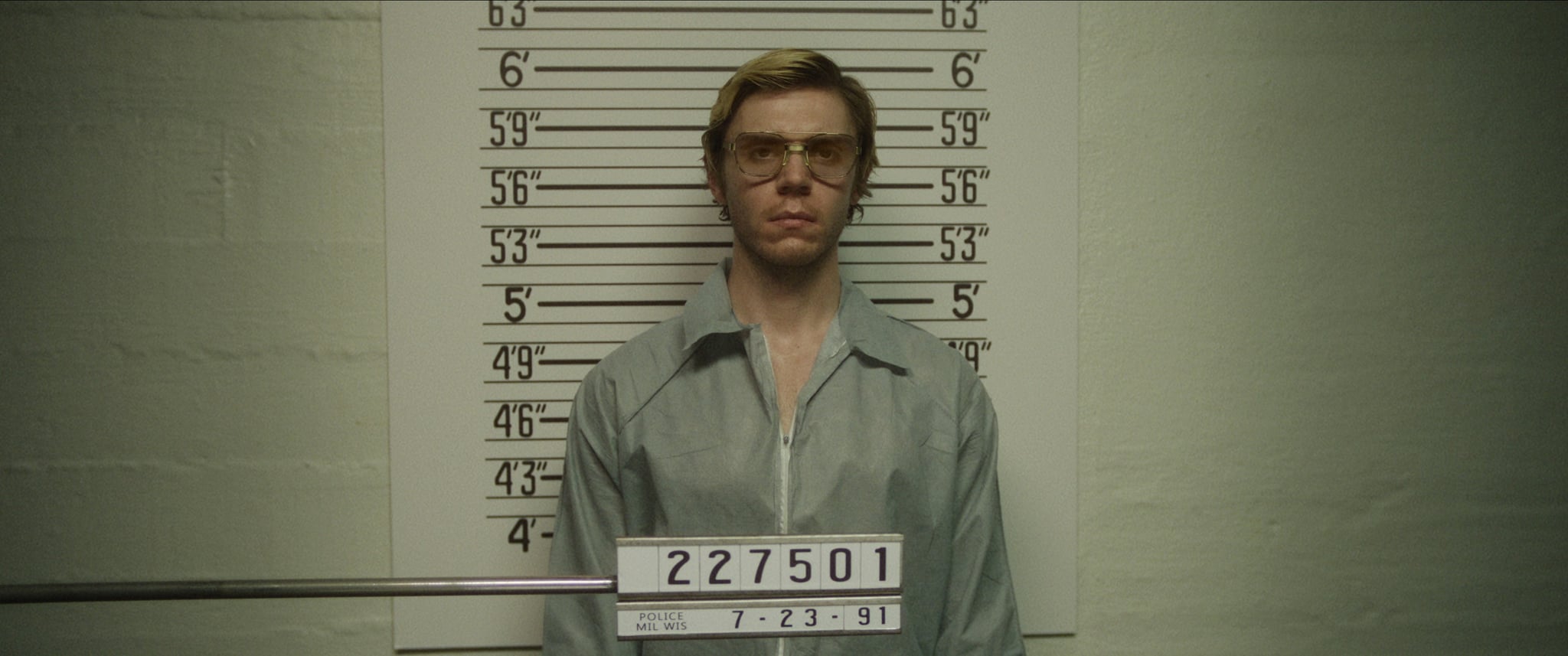

“Monster: The Jeffrey Dahmer Story” is the latest true-crime dramatization to feature a famously good-looking actor as an infamous murderer. Evan Peters stars as the titular real-life serial killer in the September 2022 release, following the likes of Ross Lynch as Dahmer in 2017’s “My Friend Dahmer,” Zac Efron as Ted Bundy in 2019’s “Extremely Wicked, Shockingly Evil and Vile,” and many others. But despite its high production value, successful ratings, and supposed aim to educate its audience, the series is sparking long overdue conversations about how true-crime dramatizations tend to capitalize on shock value, exploit victims while romanticizing perpetrators, and ultimately do more harm than good.

Jeffrey Dahmer was a serial killer who murdered 17 young men and boys between 1978 and 1991. He sought out his victims — mostly Black, Latino, and Asian men — at gay bars, bus stops, and malls, luring them into his home and drugging them before strangling them to death. After killing his victims, Dahmer would engage in necrophilia, dismember their corpses, and eat their tendons. Dahmer was eventually tried in 1991 and sentenced to 16 life terms. He was beaten to death in prison by a fellow inmate in 1994.

Several dramatizations of Dahmer’s life have been made, including “The Secret Life: Jeffrey Dahmer” in 1993, “Dahmer” in 2002, and “Raising Jeffrey Dahmer” in 2006, so “Monster” was by no means the first depiction of the serial killer’s story. But the series’ shot-for-shot recreation of court footage, victim-focused episodes, graphic violence, and overwhelming success have made it a standout. In fact, the Ryan Murphy-produced drama was heavily promoted and became Netflix’s second most-watched original in a week (only behind “Stranger Things 4″).

It’s not all that surprising, as dramatizing shocking real-life events is a way to generate buzz — and that’s certainly the case with “Monster.” A troublingly large amount of Twitter and TikTok users are fawning over Dahmer’s looks, posting side-by-sides comparing the series to reality, and even sympathizing with Dahmer despite his heinous crimes. And as the show gains popularity, so has music that references Dahmer’s murders. Katy Perry and Juicy J’s 2013 hit “Dark Horse” features the line, “She eats your heart out like Jeffrey Dahmer,” and a lyric in Kesha’s 2010 song “Cannibal” says, “Yeah, I’ll pull a Jeffrey Dahmer.” Both songs, particularly their Dahmer-related lines, have seen a resurgence on TikTok, a slap in the face to Dahmer’s victims and an unpleasant reminder that Netflix dramatizations aren’t the only medium guilty of making light of Dahmer’s crimes. Altogether, the buzz created by these dramatizations is often incredibly insensitive to the victims’ families.

Rita Isbell, whose brother Errol Lindsey was murdered at 19 by Dahmer, criticized Netflix for profiting from her family’s tragedy. In an essay for Insider, Isbell recalled seeing her emotional court outburst play out on screen in the dramatization (portrayed by DaShawn “Dash” Barnes). “It bothered me, especially when I saw myself — when I saw my name come across the screen and this lady saying verbatim exactly what I said. If I didn’t know any better, I would’ve thought it was me,” she wrote. “Her hair was like mine, she had on the same clothes. That’s why it felt like reliving it all over again. It brought back all the emotions I was feeling back then.” Isbell revealed she was never contacted about the show, saying, “I feel like Netflix should’ve asked if we mind or how we felt about making it. They didn’t ask me anything. They just did it.” She criticized Netflix for profiting off of Dahmer’s victims without giving any money to their families, specifically their children, calling it “just greed.”

Despite victims feeling exploited by true-crime adaptations, these stories continue being made without their consent — and are often praised. Unfortunately, it seems most networks are averse to consulting with victims. It can be done, though. The upcoming Peacock series “A Friend of the Family” dramatizes the story of Jan Broberg, who was kidnapped by Robert Berchtold when she was 12 and then again when she was 14. Broberg and her mother, Mary Broberg, served as producers of the show. So why don’t more true crime series consult with victims? It’s likely because seeking consent would either stop the project in its tracks or require the creators to gut-check their storytelling instead of telling the most dramatic and shocking version they possibly can.

The re-emerging relevance of Dahmer is a consequence Netflix must have seen coming before “Monster”‘s release. It’s likely why they angled it as a dramatization meant to educate viewers about the social issues that plagued the justice system at the time that allowed Dahmer to get away with his crimes for so long. In September, Evan Peters told Netflix Queue, “It’s called ‘The Jeffrey Dahmer Story,’ but it’s not just him and his backstory. It’s the repercussions; it’s how society and our system failed to stop him multiple times because of racism and homophobia,” adding, “Everybody gets their side of the story told.”

However, that logline falls flat. While the series may not be exclusively about Dahmer, it is named after him, features a photo of only him on the poster, and focuses largely on him throughout. The series also features several brutally violent scenes in which Dahmer decapitates people, kisses their severed heads, rapes their dead bodies, and eats their remains. Although the perspectives of victims are explored in the series, particularly in an episode about Anthony “Tony” Hughes, it’s essential to consider if the victims’ stories are actually being told by those qualified to tell them — their families. In this case, they weren’t. If they were, chances are the dramatization wouldn’t have alternated rapidly between humanizing the victims and treating them as expendable characters murdered in a slasher movie — a portrayal no family member should have to see. These victims were real people whose stories should be treated with humanity and sensitivity — not exploited for shock value.

Of course, highlighting the racism that allows white men to commit violent crimes with little suspicion by law enforcement is important, as is highlighting how young Black men are victimized most — a reality that may come as a surprise to many considering true crime tends to focus on the stories of white female victims, capitalizing on what the late PBS news anchor Gwen Ifill famously called “missing white woman syndrome.”

True crime scholar Jean Murley told The New Yorker that true crime is a “white genre,” explaining, “This is white America telling itself a story about danger and violence and womanhood, when the fact is that most homicide victims in this country are young men of color, and those stories don’t get told, by and large. They just get ignored. They get trivialized: ‘Oh, it’s drugs, crime, gangs, urban violence.’ But then a white woman goes missing, and that’s a big deal.” This is why many of “Monster” ‘s supporters are taking the stance that portraying crimes against young Black men, who have the highest homicide victimization rate as of 2005, is much needed in 2022. While that’s true, “Monster” doesn’t exactly follow through sensitively. Instead, the series exploits the victims without consent and tells the story through the skewed lens of the white murderer.

Fighting for fair representation of young Black men (as well as women, and nonbinary people) as victims of crime the same way that white women are in true crime movies and TV is a worthy cause. But to do this, it’s necessary to do so sensitively and not re-exploit the victims in the process.

There isn’t much of a mystery here — the families are telling the public directly that they are being harmed by “Monster.” Relying on the brutal murders of real people, told from the perspective of the murderer, isn’t just exploitative: it’s lazy and greedy.